A Cultural Foundation

Over eighty artistic estate collections and material on more than eighty thousand names spanning the history of the cabaret and its predecessors comprise the core of the German Cabaret Archives. Founded in 1961 by Reinhard Hippen in Mainz, the private collection transferred to the city of Mainz in 1989. Meanwhile, under the direction of Jürgen Kessler, the archives have been transformed into a cultural foundation subsidized by several public institutions. Since 1999, in recognition of their national importance, the Cabaret Archives have been supported by funding from the Cultural and Media Deputies of the Federal Government. The collections moved to the historical Proviant-Magazin warehouse building in Mainz in 2004.

The Bernburg Collection

A second branch in Bernburg on the Saale River documents the history of the cabaret in the German Democratic Republic. This project is supported by the city of Bernburg and the Federal Government. The archives are located next to the “Eulenspiegel Tower” in the Christiansbau of the Bernburg Palace.

Stars of Satire

In their museum areas, both branches of the archives memorialize major figures of the cabaret in the twentieth century and present the “Stars of Satire” in their permanent exhibits. Mainz has honored the “immortals” of history in a cabaret “Walk of Fame” that runs between the Proviant-Magazin and the Unterhaus Theater, while a “Hall of Fame” in the Bernburg Palace has a similar mission.

GERMAN CABARET ARCHIVES

Documentation Center for German-Language Satire

Since 1961

Purpose | The playful, satirical form of cabaret and its literary, philosophical, and poetic qualities are the focus of our documentary interest. The central task of the German Cabaret Archives is the continuous collection and the availability of these materials to academics and historians.

Queries are answered on a daily basis, and scholars visit from around the world. First of all the archives serve as a research site and source for studies, dissertations, and theses in the fields of Literature and Theatre, as well as Musicology, Linguistics, Cultural History, and Politics.

Exhibits of the archives’ collections tour Germany regularly. They have been seen in Switzerland, Austria, Luxemburg, France, Poland, Israel, Japan, and Australia. The six-part series “100 Years of Cabaret” was opened in 2001 in Berlin’s Academy of the Arts. In light of the huge demand, two versions of this touring exhibit are now available, and with help from the Maison Dijon de Rhénanie-Palatinat part of the material is being translated into French.

A special exhibit on the theme of “Cross-German History in the Mirror of Political Cabaret: Divided Mockery, Shared Laughter” was commissioned by the Federal President on the occasion of the National Day of Unity.

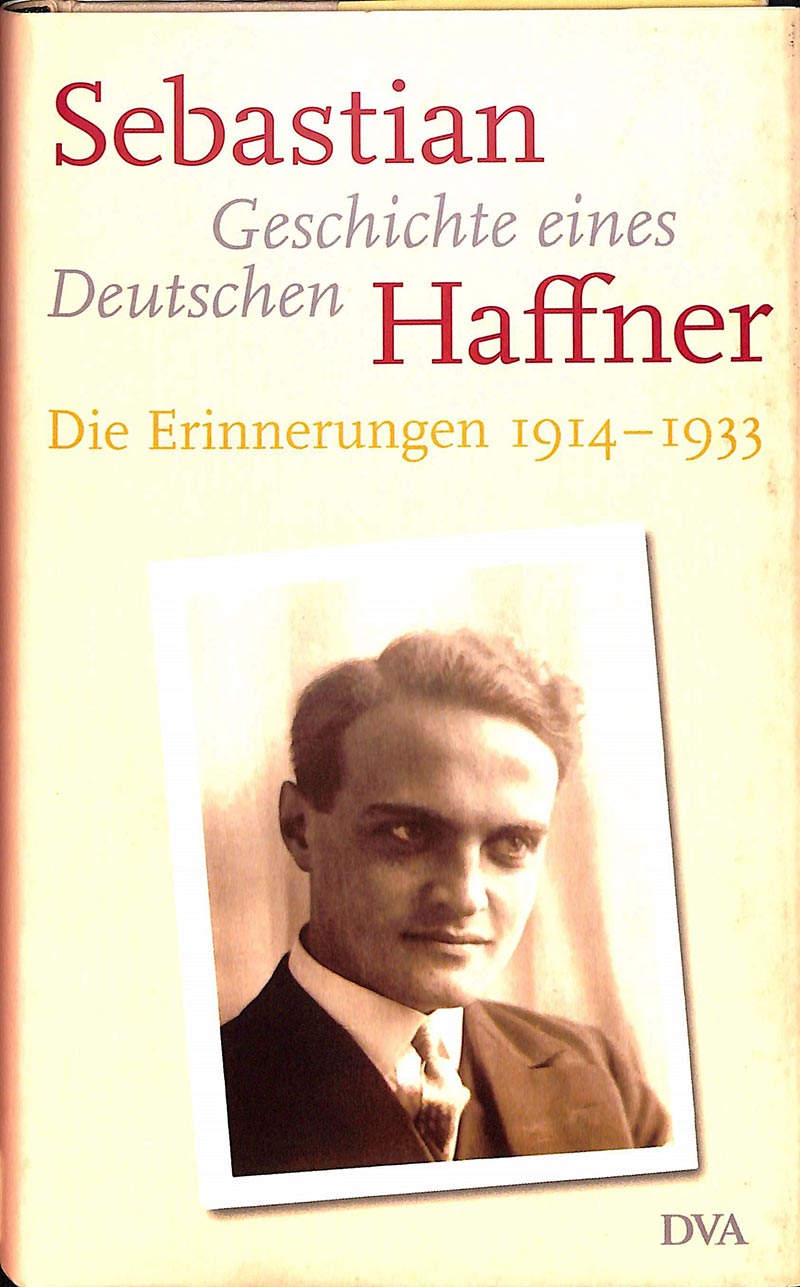

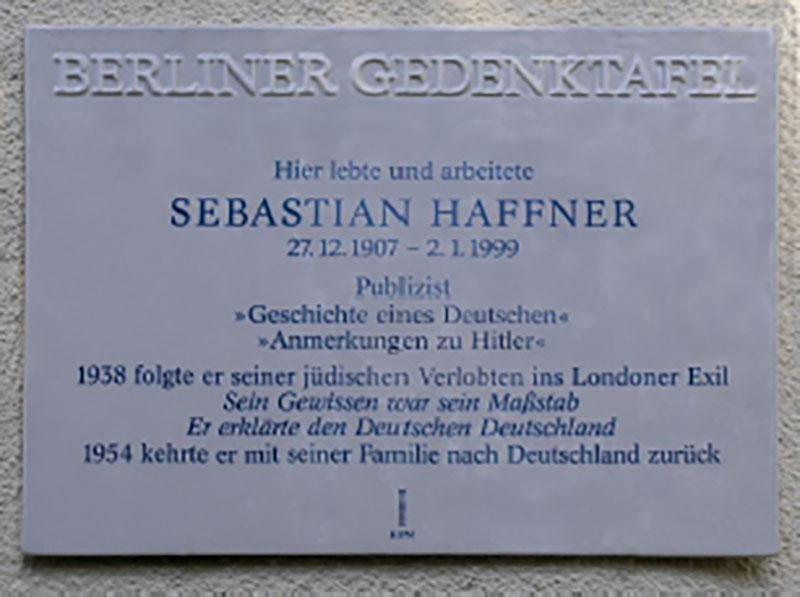

Cabaret in Germany

officially began on January 18, 1901. The German Cabaret Archives document its history: What the cabaret was, what it became, and what it is. And what it can be, even in systems of oppression and intolerance.The year 2018 is the eightieth anniversary of the so-called “Night of Broken Glass,” a euphemism for the night of November 10, 1938. And 85 years ago, May 10, 1933, was the day when books burned in Berlin. Shortly thereafter, on June 23, they burned in Mainz as well. In his memoirs, “Defying Hitler: A Memoir”, Sebastian Haffner describes what literary-political cabaret could be during the years of the National Socialist reign of terror.

Incidentally,

it is typical of the early years of the Nazi regime that the whole façade of everyday life remained virtually unchanged. … The fact that this was possible also speaks against us. Our reaction to the experience of fearing for one’s life, and being totally at the mercy of events, was only to try and ignore the situation and not allow it to disturb our fun. I think a couple of a hundred years ago would have known better how to deal with such an experience—if only by celebrating a great night of love, spiced by danger and the sense of loss. Charlie and I did not think of doing anything special, and just went to the cabaret because nobody stopped us: first, because we would have gone anyway, and second, in order to think about unpleasant things as little as possible. That may seem cold-blooded and daring, but it really only indicates a weakness of the emotions. We were not equal to the situation, even as victims. If you will allow me this generalization, it is one of the uncanny aspects of events in Germany that the deeds have no doers and the suffering has no martyrs. Everything takes place under a kind of anesthesia. Objectively dreadful deeds produce a thin, puny emotional response. Murders are committed like schoolboy pranks. Humiliation and moral decay are accepted like minor incidents. Even death under torture only produces the response “Bad luck.”

That evening,

however, we were recompensed for our inadequacy beyond our deserts. Chance had led us to the Katakombe, and this was the second remarkable experience of the evening. We arrived at the only place in Germany where a kind of public, courageous, witty, and elegant resistance was taking place. That morning I had witnessed how the Prussian Kammergericht, with a tradition of hundreds of years, had ignobly capitulated before the Nazis. In the evening I experienced how asmall troop of artists, with no tradition to back them up, saved our honor with grace and glory. The Kammergericht had fallen but the Katakombe stood upright.

The man

who led this small group of artistes to victory—standing firm in the face of overwhelming, murderous odds must be counted as a victory—was called Werner Finck. This minor cabaret master of ceremonies has his place in the annals of the Third Reich, indeed one of the very few places of honor there. He did not look like a hero, and if he finally became something like one, it was in spite of himself. He was not a revolutionary actor, had no biting satire; he was not a David with a sling. His character was at bottom harmless and amiable, his wit gentle, light, and capricious. His jokes were based on double entendre and puns, which he handled like a virtuoso. He had invented something that could be called the hidden punch line. Indeed, as time went by it became more and more necessary for him to hide his punch lines, but he did not conceal his opinions. His act remained full of harmless amiability in a country where these qualities were on the liquidation list. This harmless amiability hid a kernel of real, indomitable courage. He dared to speak openly about the reality of the Nazis, and that in the middle of Germany. His spiel contained references to concentration camps, the raids on people’s homes, the general fear and general lies. He spoke of these things with infinitely quiet mockery, melancholy, and sadness. Listening to him was extraordinarily comforting.

This March 31

was perhaps his greatest evening. The house was full of people staring at the very next day as if into an abyss. Finck made them laugh as I have never heard an audience laugh. It was dramatic laughter, the laughter of a newborn defiance, throwing off numbness and desperation, feeding off the present danger. It was a miracle that the SA had not long since arrived to arrest everybody here. On this evening we would probably have gone on laughing in the police vans.We had been improbably raised above fear and danger.Translated by Oliver Pretzel, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York 2002

Take a peek…

You’ll be surprised when you visit me in the historic Commissariat in Mainz. I’m anything but the cliché of a dusty archive. Despite my youth, I am a classic, if I may say so myself. Permit me to present myself in over a thousand square feet of downright museum elegance. Just for you, of course! After all, I have a mission. In the cultural interest of the public. I preserve an entire genre, a unique art form, so to speak! My founder registered me in the family genealogy as a “documentation center for German-language satire.” Just after he arrived in Mainz in 1961, he proudly named me the “German Cabaret Archives.”

Since that day,

my staff has been dedicating themselves to the performance forms and manifestations of satire around the world. That’s why we so often greet international visitors. Recently a student from Moscow was here to hunt for material from the 1920s for her doctoral dissertation, and a professor from Japan was interested in the cabaret in exile. Once a doctoral candidate from Yale University spent nine months in the bowels of the archives tracing the role of the medieval troubadour as an ancestor of the political singer-songwriter. Written inquiries from all over the world testify to the great interest in my treasures. That’s why I was able to open over 160 exhibits since the beginning of the 21stcentury, in seven European countries. Including France. In the Maison Heinrich Heine of the Cité Universitaire Internationale de Paris: “Le Monde, un Cabaret –Les débuts du cabaretlittéraire en Allemagne et en France.” Montpellier, Toulouse, Lyon, and Dijon followed. In the German-speaking regions, we toured with “100 Years of Cabaret” from Alzey to Zurich. That exhibit shows what I have to offer: the genre! Its manifestations. Their history. It’s about the artists. Especially about the political-literary cabaret as an art striving for democracy and freedom. It’s about the authors. Their life stories. All too often they were stories of suffering. It’s about their relevancefor interested people from all eras. For the audience of the Belle Epoque. Of the imperial era. Between revolution and censorship. Between the First and Second World Wars. Between democracy and dictatorship, militarism and fascism. It’s about the art of survival. In exile and under cover. Between styles and between political

parties. It’s about our culture. About its transformations. About education. And of course it’s about laughter. Laughter at ourselves and at everyone else. It’s about thetopography of mockery and its language through the changes of the times. Just like it’s about the humor and poetry of our human experience. About the absurd and the concrete. About criticism of current affairs in artistic form. And last but not least,it’s about entertainment too. From the very beginning. And about love! Collecting, by the way, is a form of love, the American philosopher George Steiner once said.

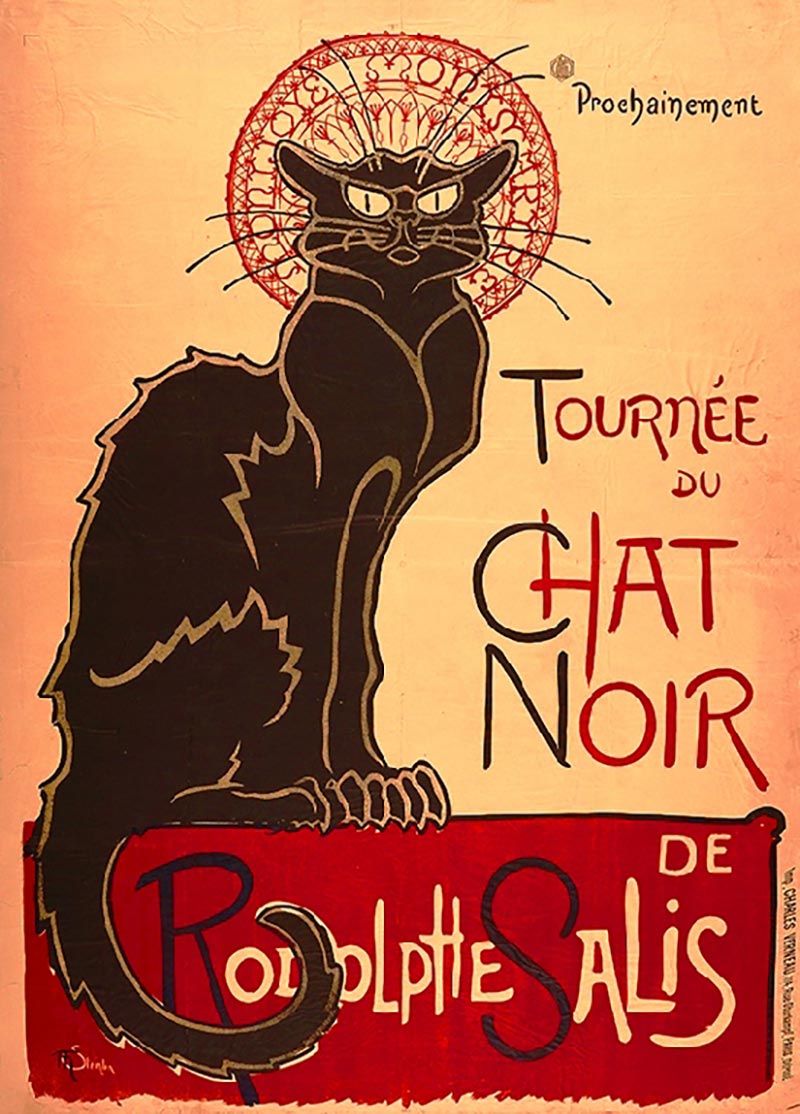

The cabaret’s composite form of different stage genres

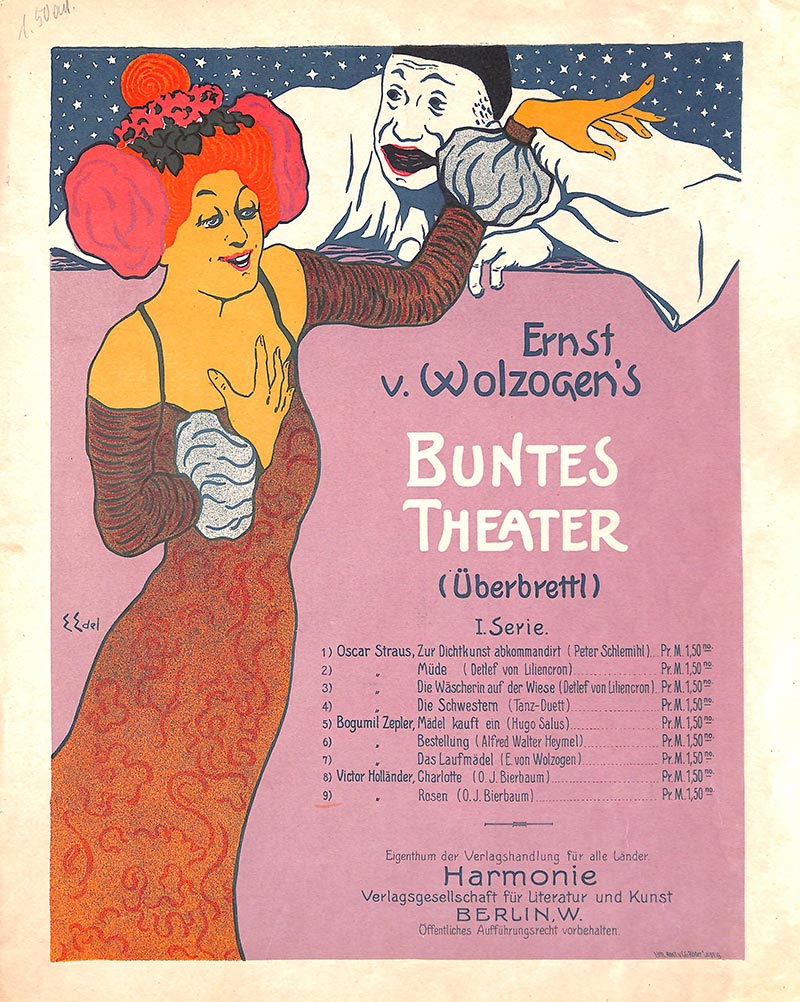

has, in a formal sense, only existed since the end of the nineteenth century. This mixture is symbolized by the lovely French term “cabaret.” That means, on the one hand, a pub, a little bar, and that includes its intimate character. On the other hand, it means a divided salad platter, an hors d’ouevres tray. The sections around it represent the different stage arts: music, theater, dance, sketches, even painting. After some predecessors like the “Cabarets des Assasins,” where they sang street ballads about murderers, it was Rodolphe Salis, originally a painter, who climbed up onto a barrel one night in the fall of 1891 in his pub “Chat Noir” in Montmartre and announced the performances of various artists for his well-heeled audience. That was the birth of what the world now knows as the topical, literary cabaret! As the founder of the so-called Cabarets Artistiques, Salis was the first of his guild of emcees. You could call him the connecting sauce in the center dish of the divided salad platter. His commentaries were notorious! Sometimes insulting, aggressive, just like the songs sung there. But that’s what attracted the intellectual public of Paris. Soon the intellectual elite climbed up to the “Butte sacré.” Politicians and aristocrats followed. For example, Victor Hugo and Émile Zola; the Italian freedom fighter Giuseppe Garibaldi came, as did Prince Jérôme Bonaparte, the great-nephew of the great Napoleon and the nephew of Napoleon III. Many singers, composers, and performers of great talent appeared, most of whom later became famous, for instance Aristide Bruant and Yvette Guilbert, the first diseuseof the French cabaret. Her male counterpart Aristide continued his career in his establishment “Le Mirliton” with socially critical songs aimed at the hypocrisy of the propertied bourgeoisie. Thanks to a poster by Henri-Lautrec, he’s world famous today. Two Chat Noir posters from 1895 recently arrived in my graphic cabinets, joining all the others, almost twenty thousand artifacts from all eras of the twentieth century. It all started with a segment of the population that loved art and culture. Cabaret was, at least for the bohemians, the medium of choice. The author Otto Julius Bierbaum proclaimed: “The renaissance of all the arts and of life from the music hall! We’ll dance up a new culture! We’ll give birth to Superman in the honky-tonk! We’ll knock this silly world on its butt!” He meant it seriously! Unfortunately, it was other people who knocked the world down. But still, it

was something new for 1900! It was the era of new beginnings, of new inspirations: mankind as beings hurled into time. The world as a cabaret! Like art nouveau, this new art form gave rise to a downright movement—it was “in” and “en vogue,” and it became a fashion that soon swept into Berlin. Here the conservative baron Ernst von Wolzogen had a hit with his “Überbrettl” on January 18, 1901, the thirtieth anniversary of the founding of the Second GermanEmpire. The theater regulations of this stage are in our archives.

Soon afterward,

the “Eleven Executioners” entered the scene in Munich: the first real political cabaret in Germany. Frank Wedekind joined the eleven, as did Marc Henry, who hailed fromParis. So my immediate ancestors come from France on my mother’s side and from the German Empire on my father’s side. A European mishmash just like old royalty… And then it went fast! By 1901 forty locales had developed along the Spree river with programs of literary cabaret. In Vienna, “Zum lieben Augustin” (Dear Augustine), the “Nachtlicht” (the Nightlight), and the “Fledermaus” (the Bat) opened. Frida Strindberg, whose first child was fathered by August Strindberg and her second by Frank Wedekind,founded the first cabaret in London. Before that, Barcelona had “El quatre Gats.” Cracow, Warsaw, Budapest, and St. Petersburg: cabarets on the French model developed all the way to Moscow. Wherever business savvy and a knack for artistry were lacking,though, a newly opened locale often quickly failed. But the upswing prevailed. At first. Typical for this young art form, as originally in Paris, was the pub stage, the podium for the so-called vagants or goliards. Here the dream of the artistic bohemians was realized: presenting their own works, free and outside of the established art business. The immediacy of this art form on stage is fascinating. Theater pretended things for the audience, but in the cabaret they speak directly to the audience! Salaries for the performers were generally rare. Most people got paid in food and drink. Or they passed around a collection plate. Apropos troubadours: the models and roots went way back into the middle ages. Moral and satirical poetry, love and drinking songs of the so-called Erzpoeten,the earliest poets. In Hanns Dieter Hüsch’s “Arche Nova,” the role of the “archipoeta” was honored in the very first program booklet with one of his songs from the twelfth century. The most important collection, about three hundred songs, discovered in 1803 in the Benediktbeuren monastery and called “Songs of Beuren,” gained international fame with a new musical setting: Carmina Burana.Troubadour poetry as an extravagant oratorio, timeless thanks to Carl Orff’s brilliant music.

The artistic bohemians themselves are a product of their time.

And so these new cabarets live from and for the moment. Only the “Simplicissimus” in Munich is a long-lived success, run by a very competent female emcee who was also an ingenious businesswoman: Kathi

Kobus manages to synthesize art and commerce. The “Simpl” runs for fifty-six years, from 1903 to 1968—a time span that few cabarets have managed to match until today. And who hung out there there before the First World War? Just about everybody, and the stylish elite of Munich! Tourists from abroad, the Prince of Wales, Czar Ferdinand of Bulgaria, the King of Belgium, captains of industry, wealthy aristocrats. Wilhelm Voigt, the shoemaker who made a name for himself as the “Captain of Köpenick,” appears for money in the Simpl and sells his autograph. And a certain Hans Bötticher. He’s a regular, then the house author, and later he became famous as Joachim Ringelnatz.

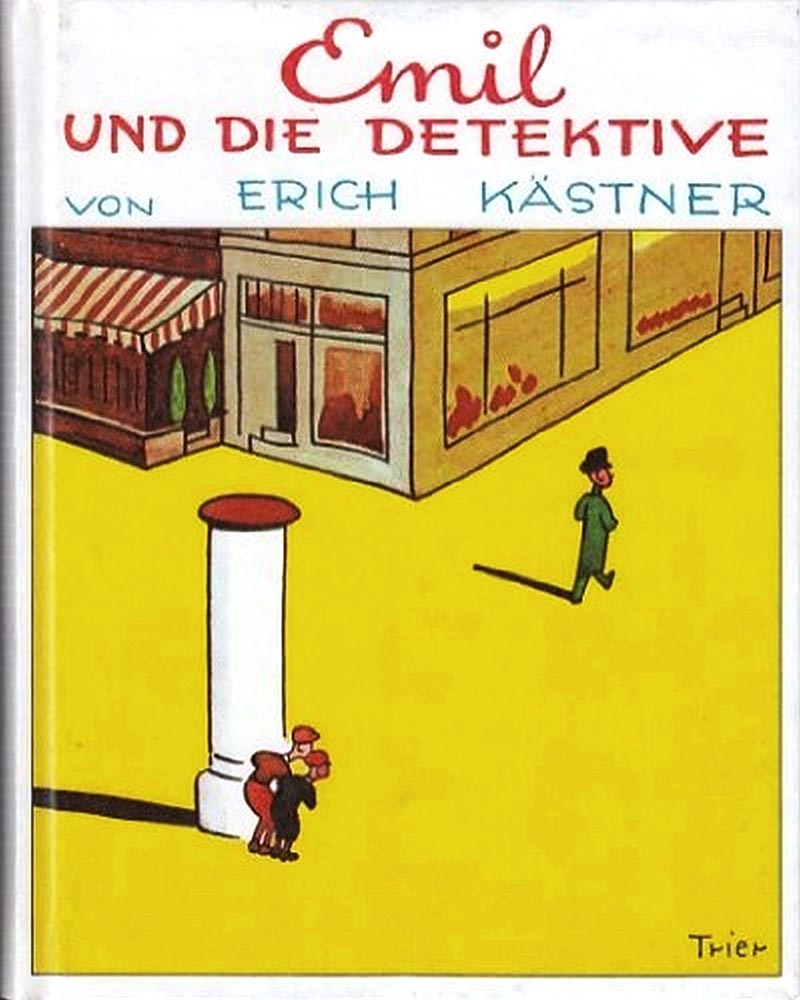

On my fiftieth birthday, a sweet, elderly lady gave me a gift, the “Golden Book of the Catacombs.” In 1929, her late husband Tibor Kasics had co-founded the cabaret “Katakombe” (the Catacombs) with Werner Finck in Berlin. In this wonderful gift there’s an amusing dedication by Joachim Ringelnatz, as well as an original drawing by Walter Trier, who illustrated the books of Erich Kästner. There are autographs and aphorisms ranging from Hans Albers to Carl Zuckmayer, by Klaus and Heinrich Mann, Walter Hasenclever and George Grosz, Max Reinhardt, Erich Mühsam, Gustav Gründgens, Luigi Pirandello and Erwin Piscator alongside Alfred Döblin and Richard Huelsenbeck.

The latter came up with the Dada recipe for cabaret:

“Dada is the cabaret of the world, just as the world, the cabaret, is Dada.” In the “Cabaret Voltaire” in Zurich, Hugo Ball invented that literary form as a challenge to the bourgeoisie’s apathy toward the horror of the First World War. After 1918, Kurt Tucholsky and Walter Mehring were the foremost cabaret authors, thechroniclers of an abandoned republic and champions of aggressive satire, who also wrote lyric poetry or hilarious humor to entertain their audience. For Bert Brecht, the cabaret served as an inspiration for his theory of epic theater. With the ditties of Otto Reutter or the songs of Friedrich Hollaender and Rudolf Nelson, sung by stars the likes of Claire Waldoff and Marlene Dietrich, the cabaret made its mark on the opulent revues and the music hall stage, especially in Berlin. In Munich, cabaret took the popular-absurd form of the uprooted humorist of the sorrowful countenance, Karl Valentin. And in 1932, a year before Hitler came to power, Werner Finck stands bashfully smiling on the stage and looks straight ahead. He’s imagining what will happen when the Nazis take over, and he predicts, “In the first weeks of the Third Reich, parades will be held. If these parades are interrupted by rain, hail or snow, all the Jews in the vicinity will be shot.” This punchline, we would soon see, was no joke.

When the Nazis come to power, Finck tries to embody humor as resistance. Hundreds of cabaret performers and satirists spend the “Thousand-Year Reich” in concentration camps. As a sampling, remember the artists that are honored with a satire star outside my front door on Romano Guardini Square in Mainz: Erich Mühsam, Fritz Grünbaum, and Kurt Gerron. They were murdered in Oranienburg, Dachau, and Auschwitz.

After May 8, 1945, cabaret enjoyed a genuine rebirth. In the western zones of “Trizonesien,” they sang with a taunting, melancholy tone: “Hurra, we’re still alive.” In the “Kom(m)ödchen” in Dusseldorf, the cabaret set new political and literary standards. Erich Kästner started writing again in Munich, and Günter Neumann’s radio cabaret “Die Insulaner” (the Islanders) at Berlin’s American broadcaster RIAS leapt into the cold war. With Wolfgang Neuss, the cabaret drummed the consequences of suppression and the economic miracle into the West German conscience, and at Munich’s “Lach-und Schiessgesellschaft” and the Berlin “Stachelschweine” (the Porcupines), they celebrated the new year in television style. In this way, cabaret becomes popular with a broad middle-class audience. Back then, television was behind the boom of political cabaret. In East Germany, for four decades, cabaret adapted to the limits of everyday censorship—convinced, when push came to shove, of the superiority of socialism. That’s a story in its own right, which now has its own roof over its head for collecting and documenting the history of cabaret in the GDR, in Bernburg Castle on the Saale River. In West Germany of the Sixties, Franz-Josef Degenhardt sang out against the rise of neo-Nazis; the cabaret of the APO, the extra-parliamentary opposition, agitated into the troubled Seventies; and finally, Hanns Dieter Hüsch’s “Hagenbuch” declared everyone and everything sick and insane.

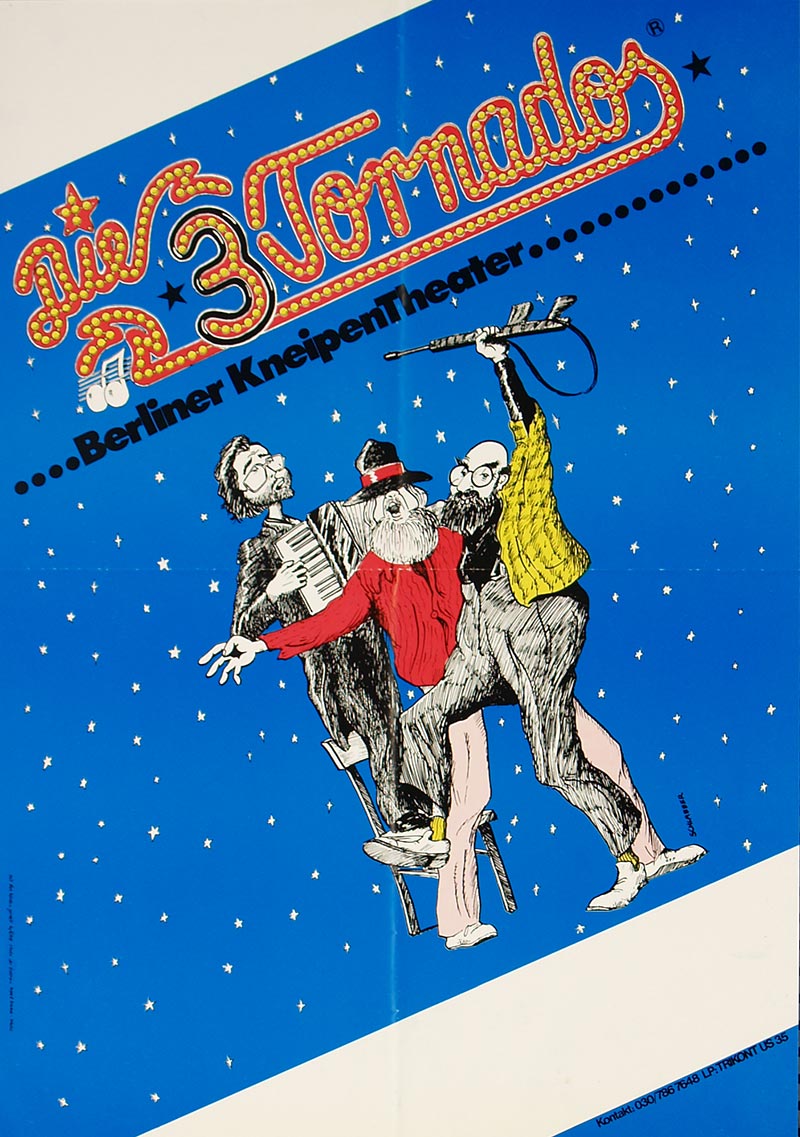

In the Eighties,

cabaret rollicked though the young Sponti activitist and alternative scene as the “Three Tornadoes.” With Thomas Freitag, it unceasingly parodied Chancellor Kohl, the inventor of Realsatire,true events that are so absurd they seem like satire, “in this here land of ours,” while with Gerhard Polt it performed an autopsy on our mental roots, and with Richard Rogler, it survived the new intellectual-moral freedom through cynicism, and on the growing commercial television networks, it discovered its market value. Since then, it has been wavering between cabaret and comedy, between meaningful political commitment and a heightened sense of profit, between Germany’s intimate stages and huge arenas. Over a hundred years later, that old “Jest, Satire, Irony and Deeper Significance” (to play on Christian Dietrich Grabbe’s comedy) with which one once hoped to topple the status quo fell prey more and more to the rules of commercial entertainment. The country has changed. New paradigms are everywhere. But that’s how it always was throughout the eras. Even constitutions don’t live up to their promises. Everything has its premises, its developments, its transitions. And eventually it has its cultural history—which I document for the cabaret. And so, Willkommen! Bienvenue! Welcome!Take a peek. Take your time. Make a reservation. Visit us. Maybe we will meet one day!